Research

These are some of the topics I’ve been working on:

Evolutionary immuno-epidemiology

In the lab of Rob de Boer, I worked on multi-level evolutionary models of both HIV and influenza A virus (IAV). Both are examples of pathogens that relatively recently jumped the species barrier, and have been adapting to their new host ever since. A remarkable aspect of this adaptation is that the host population is extremely diverse, most importantly in terms of the immune system. I developed agent-based models of HIV evolution in a heterogeneous population that were calibrated to real-life observations such as the viral load (VL) distribution, infection and disease progression rates. The high person-to-person variability of the immune system implies that each individual likely has a different immune response to the same pathogen. My model predicted that not between-host, but within-host immune pressures primarily decide the evolutionary trajectory of the pathogenicity, and that this pathogenicity is kept in check by host heterogeneity. More broadly, my work showed how diverse host-pathogen interactions could have huge impacts on both the patient and epidemiological level.

Unlike HIV, influenza causes acute infections that induce a sterilizing antibody (Ab) response. The virus can re-infect during subsequent seasons due to antigenic evolution. It evades neutralizing Abs by mutating its neuraminidase and hemagglutinin receptors. After an influenza infection, the lung tissue is also populated by influenza-specific T cells that respond to more conserved parts of the virus (epitopes). Inspired by Ab-antigenic drift, we found evidence in genetic and immunological data of similar antigentic drift in T-cell epitopes. This is important, because T cell immunity against influenza wanes primarily because the concentration of tissue-resident T cells (TRMs) drops relatively quickly. Boosting those T-cell concentrations is therefore an important therapeutic target. My work highlights evolutionary implications of such strategies.

Mathematical Epidemiology

I have worked on a number of epidemiological projects, mostly on statistical inference. For instance, during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not clear to what extent the virus was adapting to its new host, and how different non-pharmaceutical measures could impact the spread of the virus. One of the first signs of adaptive evolution was the rapid spread of the D614G mutation in the spike protein. To quantify the strength of selection, I developed a stochastic epidemic model with multiple SARS-CoV-2 strains that was fit with sequential Monte-Carlo to death incidence and genetic data from multiple regions. I co-developed simpler models that were used to fit data from many regions simultaneously to quantify region-dependent variation in selective advantage. We found that selective advantage is highly model, region, and variant dependent, and can only be estimated with certainty if the number of cases caused by the new variant is already relatively large.

Before the first SARS-CoV-2 vaccines became available, it was not well understood how quickly restrictions could be lifted. We therefore used government vaccination roll-out plans and dynamical models to compare different scenarios. I used age-dependent contact data, hospitalizations, and seroprevalence data to calibrate the models with Bayesian inference. This allowed us to quantify the uncertainty in our forecasts. We proposed timelines for relaxation of measures that would prevent large outbreaks during the vaccination roll-out.

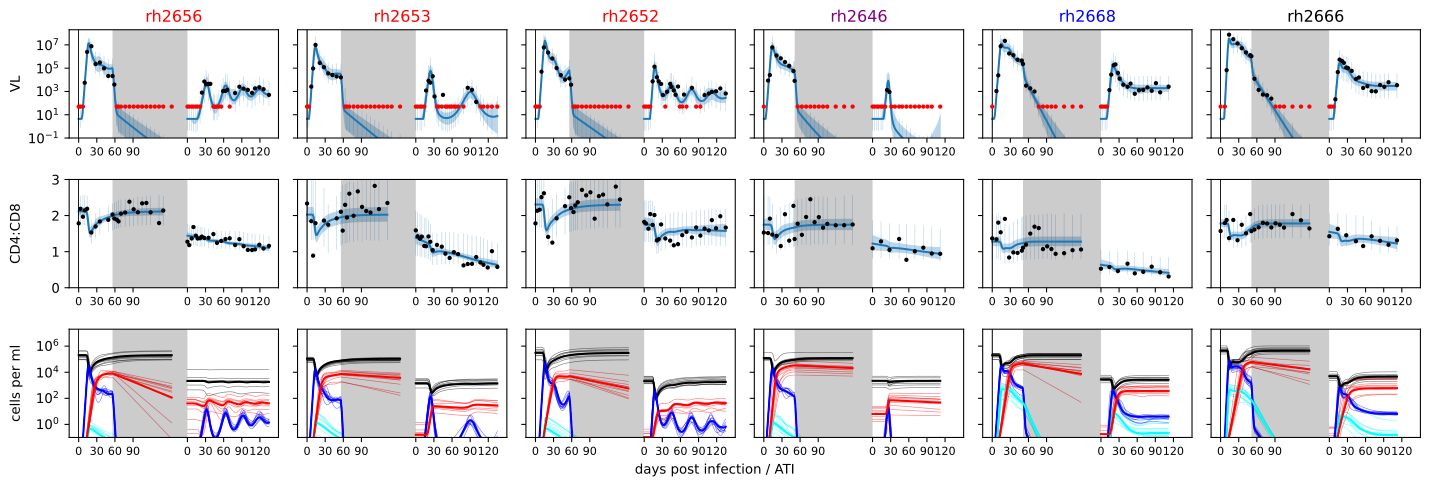

HIV rebound after treatment interruption and immunotherapy

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) prevents disease progression and transmission in people with HIV, but is not a cure. HIV persists in a reservoir of latently infected cells that reactivate and restart the infection when ART is interrupted. However, some individuals naturally control HIV without treatment, and a handful of individuals have been cured from HIV after receiving leukemia treatment. Inspired by these cases, there is currently a lot of interest in finding methods to eradicate the reservoir, or inducing control/remission through immunotherapies. During my postdoc at Los Alamos National Laboratory I built models for HIV rebound after treatment interruption, and mathematical models of immune escape to analyze data from a humanized mouse experiment. I used probabilistic modeling to derive a statistical model for when HIV remission fails, and used this model to explain data from a macaque SIV study. Such studies are used to test the impact of potentially curative treatment strategies, and modeling helps with the interpretation of the outcomes of these experiments.

The time of rebound only gives limited information about the effect of a treatment. Therefore, I also developed dynamical models to explain viral load timeseries after remission failure, and used these model to quantify and qualify the effect of a number of different treatment combinations tested in a SHIV macaque study. The model for the humanized mouse data was fit to viral load, longitudinal T cell counts and genetic data. Importantly, the genetic data contained imprints of the immune response in the form of immune escape mutations. My work clearly showed the effect of such immune escape on the viral load dynamics, demonstrating that immune escape could be a major obstacle in future HIV immunotherapies.

Resident memory T cell dynamics

T cells provide protection against pathogens by means of primary effector responses, and mitigate secondary infections through immunological memory. The T cell population is heterogeneous in terms of affinity and phenotype. How this heterogeneity is established, and how it influences protection against (future) infections are key questions for the design of therapeutic interventions. Together with the Yates and Farber labs at Columbia University, I have developed mathematical models and statistical methods to infer the T cell population structure in terms of phenotype and dynamical properties. This method uses deep learning and ordinary differential equation modeling to learn parameters directly from time series of high-dimensional flow cytometry data. This approach links more traditional population-dynamic modeling with novel single-cell based variational inference techniques. Using my method, we identified candidate T cell subsets that might maintain lung-resident T cell heterogeneity after an influenza infection in mice.

Even in the absence of an infection, resident memory T cells are constantly replenished in tissues. It is however not clear what the developmental pathway for these T cells is: how do T cells recently produced by the thymus ultimately end up in a particular tissue, with a particular phenotype? Together with the Yates lab and Seddon lab (UCL), we have used data from fate reporter mice to answer this question using mathematical models.